How not to impress your wife and family!

- sailingibis@gmail.com

- Jan 29, 2020

- 6 min read

I tucked the paperback into the helm-seat. The interruption of Conrad’s Chance first started with the gastric disturbance welling from within Lilly. From down in the forward compartment, then Grace reported a similar condition. After cleaning up Lilly’s bucket I trotted downstairs to the forward windward bunk to find Grace moaning between heaves. Luckily I delivered the bucket in the nick of time. Before the bow dug into a wave launching the two of us, while changing angle in a dangling moment and then settled into another grind against the quartering, upwind sea. A bolt of hot, yellow oatmeal poured over my hand.

“You better kiddo?” I asked and simultaneously suggested. Hopeful.

“No.” Then more oatmeal. Green this time, weighty and putrid.

Thinking back a few hours, it had been an easy downwind sail at first. We’d bid farewell to our friends Petra and Chet on Viking Princess, and relaxed, sailing south over the shallow and calm waters of the Exuma flats. Remembering incredulously, there had even been laughing. 20 knots of breeze on a gentle broad reach down the languid turquoise calm. We cut up and through Farmer’s Cut and out into the deep blue of the Exuma sound. Less laughing.

I’d just finished dumping Grace’s contribution into that North Atlantic when another frail voice called up from the aft stateroom. A quick pail washout and then a dash down to find Helen in a similar state. Polite even in distress, she apologized and then asked for a towel. My third trip to the leeward rail in 5 minutes. Thank God for the autopilot.

We’d collectively decided to lengthen an 8 hour sail from Staniel Cay down to Georgetown, into a 36 hour trip for a simple reason. Turning northeast to sail the outside route around Long Island and down past the Jumentos Cays to the Ragged Cays, and abandoning Georgetown with its promise of fresh provisions, fuel, rest, relaxation and exploration would save us five days. We could sail through the night and cover the 300 miles quickly. It seemed like a splendid decision, when the warm and sinking sun joined me in advertizing reasonable conditions several hours ago. The sea, however can be a fickle harlot, and Nature sometimes has a throaty howl.

Five foot seas aren’t too bad upwind but as the waves grew to eight and then ten feet I cursed her changing proposition. They say the crew will fail, long before the boat.

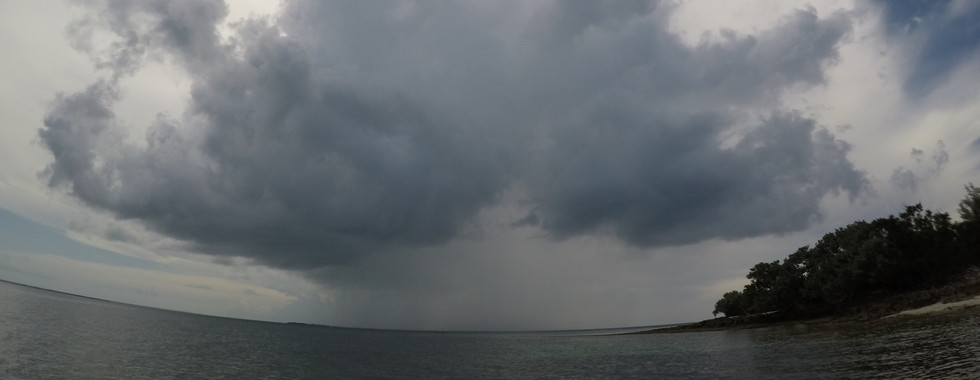

Slowly my, amazingly resolute and supportive, tribe crawled from the bowels of Ibis to join me in the cockpit and watch the sun set over a building sea. Not much was said. Looming, cold, navy shoulders marched west and behind us into the fading orange glow. Tendrils of tangerine foam caught in the waning light. I’d long put away the Genoa leaving only a bit of main and the scrawny but enforced jib. The running backstay moaned and hummed in protest against a 30+ knot apparent wind. Without uttering a word, I privately worried a bit about how our crew would handle this maelstrom with the arrival of dark. Despite the reduced sail we were running up and then through the peaking crests and spray, before digging in the troughs. We had tacked north a few hours earlier for several miles to gain some angle of advantage on the wind and shore, but now we needed every degree to clear the northern point of the approaching island. Any deviation to the comfort of a more southerly tack would plow us into the dark, rocky shoals ahead, and so we dug on into the wind. An occasional white wave would jar against the hull and spray over the cockpit. These 10 hours seemed like a week.

Amels are very tough. Built to cross oceans, Amels have sailed through hurricanes. Some most recently. While providing comfort to the mind, Ibis’s stout character contrasted with the reality of the situation: the sea often encourages the intellect and the heart to part on their own paths of reason. Ibis was built to handle, even enjoy, these conditions with a near seven foot, seven ton, winged keel beneath her and for her I had zero concerns. This was but a short trot for a young filly, an evening jog for an Olympic teen. But the waxing hours of violence seven stories above us, was wearing down my crew. The rigging wailed on like a beaten and lonely dog, close-by in the night. Tricolor light on. Pulpit light on. No stars. No moon. I offered to read, perhaps the dullest book I have worked through in the past year to the crew. Perhaps I’d distract them, and myself. By my dim, red headlight I again read Chance to ears in the darkness. I’d stop after a paragraph and report our progress toward the northern tip of Long Island. Another mile crunching into the black. They listened patiently. I was the only show in town. Pausing, I’d again reassure them and myself, once we make the turn we’d run with these beasts rather than against them. An hour passed like a day.

Then, quietly distracting my tired reading, the radar revealed a thin but persistent blip distant to the horn of the island. It was a tiny but tenacious signature, slowly moving north and directly into this building sea. I thus reasoned a large vessel, but oddly no AIS signal. Radars simply portend a mass. They do not reveal the beam, length or tonnage, they don’t tell you whether sail or power vessel. Simply that something is lurking in the ink. Five miles to our east, and in a few minutes across our bow as our ghost ship turned northwest.

Below on the radio I queried her. “Northwest-bound vessel, east of Long Island point, this is eastbound Sailing Vessel Ibis hailing you.” I reduced squelch to lonely static to hear a faint, but chipper response, “yes this is Sailing Vessel Samantha Channel 11.”

Switching, I hailed her. A jovial South African accent came through, “Yes sailing to Miami from the Grenadines… a 37 foot sloop.” This was not some 120 meter cargo ship comfortably plowing through the slop. He was rather a solo delivery captain, sailing for weeks in a small boat, now grinding upwind, alone in the night, with a turn away from weather just minutes in his future. I could feel the excitement in his voice. We chatted for a few minutes, agreed to pass “two whistles,” starboard to starboard and then wished each other well. Pondering his circumstance I returned to the helm and tried to glass him. All I could see was a wan, green glow just above the horizon wandering ever closer. One mile. And then, without acknowledgement or fanfare, we passed.

I added ten, almost imperceptible, points to our course, and put my book down to take in the moment. It was 9:30 pm. Above the dying wind I could hear the shore-break pass away off our starboard beam. Ten more clicks and slowly Ibis rose now quietly onto those marching shoulders as they slid quietly beneath her. Another 40 clicks to the south, away from the wind as the dog quietly licked its wounds. I unfurled the massive Genoa with one or two last snaps of protest against the sheet, and Ibis leaned into now softly rushing seas.

“Dada, I’m hungry!” came from a corner of the cockpit. “Me too!” from another corner. I laughed!

Is it worth it?

I’ve always shared Nietzsche’s opinion. But the stakes are much greater, and more complicated when you’ve closed your practice and sold your car, and sold your family on the idea, or rather sold a lot of your own family-political-capital for the idea. Successes are multiplied by four souls, but conversely, failures are multiplied by innumerable judges. Only time, and my beloved wife and girls can reasonably evaluate our, my gamble. We believe, only when mettle is really tested does it reveal to ones self the extent of personal durability, but it does more: it anneals that durability into a stone of quiet, confidence and pride. I argue, and mostly with myself, what more could you give a kid in this world?

What is the cost of this gift? Its value is worth only the risk of the investment.

After a light dinner the girls and Helen went below and enjoyed some sorely earned sleep, and I was left alone with my thoughts, a rising moon, and an eerily blank radar and AIS screen. Flying fish skipped and skimmed with Ibis in the moonlight, bioluminescence trailed behind our guiding rudder. Running down the sea on a broad reach is like riding your bike down an infinite hill, with the wind, and occasionally even the world at your back. And oftentimes life is just this, this quiet joy. But as certain is calm are tempests. Perhaps however, when we’ve left these ladies and they’ve matured to grown women, with a gale or worse, on the nose, they may reach down to find that stone of calm confidence and smile.

Comments